Filing freedom of information requests can seem daunting for first-timers, especially for freelancers who worry about sinking time and resources into ventures that might not pay off. Yet at a time when our fundamental right to a free press is under attack, reporters need every tool at their disposal to monitor the daily operations of government. FOIA is a critical tool not just for journalists but for democracy.

Filing freedom of information requests can seem daunting for first-timers, especially for freelancers who worry about sinking time and resources into ventures that might not pay off. Yet at a time when our fundamental right to a free press is under attack, reporters need every tool at their disposal to monitor the daily operations of government. FOIA is a critical tool not just for journalists but for democracy.

That message ran through a workshop hosted last month by CUNY Law School, the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY and the Society for Environmental Journalists. In the day-long seminar, “Separating Facts from Fake News: Environmental FOIA in the Trump Era,” veteran journalists, environmental lawyers and scholars offered a crash course on FOIA. (Most of the workshop was captured on video and as #FOIAFacts on Twitter.)

Our right to government transparency was not always a given, CUNY law professor Sarah Lamdan pointed out. FOIA was the brainchild of John Moss, a California congressman who denounced government secrecy during the Cold War, when federal officials classified more and more documents, making the business of government increasingly opaque. Despite years of campaigning for legislation to require government transparency, Moss failed to find a Republican co-sponsor until Lyndon Johnson, a Democrat, assumed the presidency. Suddenly a young Donald Rumsfeld, then an Illinois congressman, signed on because he believed, the Chicago Daily News reported, Johnson’s policies made the law necessary.

Johnson signed the law, begrudgingly, on July 4, 1966, while urging limits on its power in his signing statement. The law’s scope has expanded and contracted ever since, tracking changes in the political landscape. As records once again started disappearing during the Watergate crisis, “Congress passed a huge amendment to make the Freedom of Information Act stronger,” Lamdan said, only to see President Ford veto it as unconstitutional and risky. But Congress overrode Ford’s veto, codifying many of the transparency tools we use today. The 1974 version set limits on how much agencies can charge for records, required responses within 20 days and allowed people to sue for withheld records.

Trump, unlike his predecessors, never issued a memo outlining a position on transparency, Lamdan said. But his administration’s actions speak volumes. Let’s just say, the Trump administration is not a friend of FOIA.

But FOIA, thanks to amendments passed under the Obama administration, requires a presumption of disclosure as a first step: agencies must lean toward releasing rather than withholding records and documents. And with an administration seemingly intent on dismantling not just regulations but also the machinery of government itself, reporters can’t afford to pass on a powerful tool that makes those actions visible to taxpayers — who have a right to know what their government is doing.

Tips and tricks to bring home the documents

No one disputes that successful FOIA requests can take time and effort. You need a working knowledge of the federal Freedom of Information Act, 5 U.S.C. §552, to understand what you can and can’t ask for. You need to think carefully about what you want (and how it might serve a story), whether an agency actually has what you’re looking for and how to frame a request to maximize the odds that you’ll get it. You need to be persistent — don’t hesitate to pester the FOIA officer handling your request. And, above all, you need to be patient.

I’m still waiting for FOIA officers at the Environmental Protection Agency to finish sending me “responsive documents” (as they’re called in FOIA parlance) for a request I filed last June. Luckily, because I asked the officer to send documents on a rolling basis, as he processed them, I had enough evidence to build a case that the EPA relied on flawed science from Monsanto to register a weed killer that’s caused widespread damage to crops, family farms and wild plants throughout soybean country. That story ran in November, but I may well have follow-ups to pitch as more documents come in.

Experts at the workshop focused on using FOIA to pry records from environmental agencies, but much of their advice applies to any federal agency. Among the tips and tricks you can start using right away:

Be specific. Don’t just say, “I want all the emails between the Department of Interior and outside parties on national monuments.” Think about who’s most likely to provide insight on policy decisions. And come up with specific search terms. The narrower, the better.

It helps to put yourself in the shoes of the person handling your request, said Eric Lipton of The New York Times. Think about how you would run a query if you had access to a federal email system. For a story about industry influence over the EPA’s pesticide office, Lipton asked for correspondence between one person at the agency — Richard Keigwin, head of the Office of Pesticide Programs — and industry players and lobbyists, using the outside parties’ email domain names as a roadmap. “The officer goes to this individual’s email account and does queries on those domain names, Whatever emails come up from those domain names are the emails that are going to be produced as part of this FOIA request,” Lipton said.

“That’s very helpful to the officer, because if I were to just say, ‘Give me all emails to Richard Keigwin that have to do with pesticides, well the guy’s in charge of the pesticides program, so I mean, how many emails is that going to be? How many thousands of pages?” Limit your requests to those parties you think have an interest in the issue you’re investigating.

Be specific about dates, too, but don’t limit the end date, advised ProPublica research editor Derek Kravitz. “The end date should always be until this request is finally fulfilled,” Kravitz said. “It should never be a specific date because they can use that, wait a year and then only give you that limited date range. And that can hurt you in the newsgathering process.”

Simplify, simplify. Agencies tend to classify requests. The EPA divides them into simple, complex and expedited, and each has different average response times. The average number of working days it takes to complete a complex request for EPA headquarters is 267 days, Lipton said. The average response for a simple request is 27 days.

If you put in a very narrow request by, for example, specifying email correspondence between two people on a given date, involving a specific issue or subject line, you’ll get it back in a matter of weeks, he advised. “If you really want something quickly, you can do a simple request and you may get it really, really fast.”

Ask for electronic records. The Center for Public Integrity’s Jie Jenny Zou recommends asking for “electronic and machine-readable records.” That prevents agencies from giving you a photo of a record, forcing you to try to run them through an optical character recognition program, which is time-consuming and may not catch everything. “And if you are requesting data,” she said, “try to ask for data in its native format or nonproprietary format. So instead of Excel, ask for a comma-separated-values file, or csv file.”

Befriend the FOIA officer. Don’t just rely on email. Pick up the phone. FOIA officers can tell you what limitations they’re operating under and help you narrow search terms, dates or names to produce documents on a reasonable timeline. I’m on a first-name basis with an EPA FOIA officer who even brought in his supervisor to help me get documents I was after.

If you’re a freelancer and your request seems hopelessly stalled, don’t hesitate to drop names, Zou said. FOIA officers often aren’t familiar with ProPublica, she said, but they know its collaborators, like the Associated Press. When she mentions big-name partners, documents magically materialize. “A freelancer can do that too, if you have a relationship with an editor for a strong publication,” Zou said.

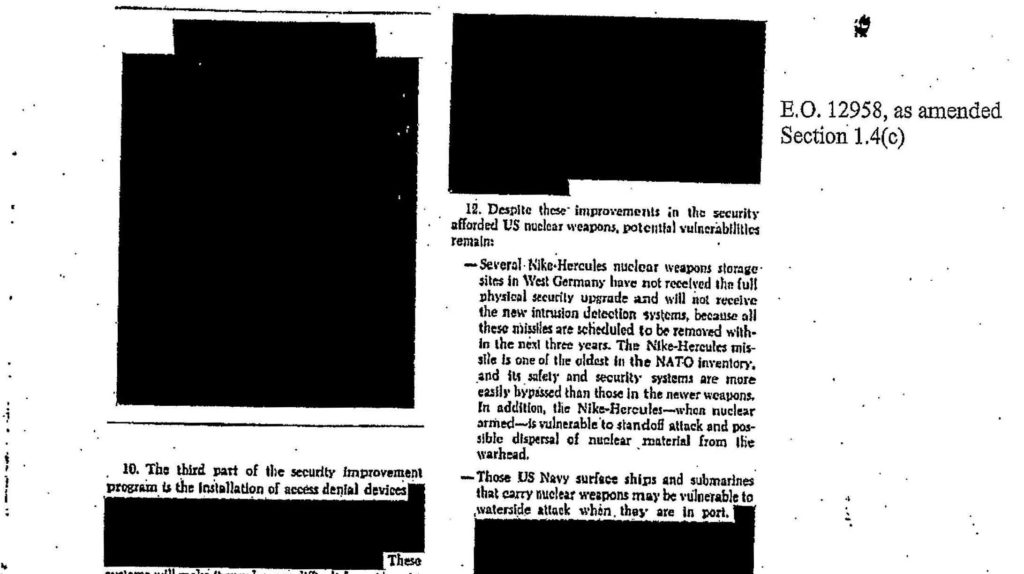

Ask agencies to justify redactions. Suing an agency to challenge redacted materials isn’t a practical option for journalists who don’t have access to the legal resources of a major outlet. But Kravitz suggests a workaround: the Vaughan Index, a document agencies prepare in opposing the disclosure of information under FOIA. “You can request a Vaughan Index, which will literally go through every exemption, every redaction on every page, and give a justification as to why they feel that meets the exemption criteria,” Kravitz said.

You can use the justifications to challenge the redactions or to report on the agency’s failure to disclose. You can also triangulate by filing matching state public records requests or requests to other federal agencies to see if their redactions match. Most likely they won’t, since the redaction process is subjective. Then you can try to piece together all the unredacted parts to see if they tell a story.

Ease into the FOIA process by piggybacking on other requests. Federal agencies log all their FOIA requests. You can ask for an agency’s log to see what other people have asked for on an issue you’re interested in, Then ask for records that look promising.

For a story about the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, The Times’ Lipton asked for the agency’s FOIA log and saw that a person with the Project on Government Oversight was asking for the BSEE director’s speeches while reporters at major outlets were asking for other aspects of BSEE’s operations. “Once these FOIAs have been produced and completed and the documents are done, you could go to the FOIA officer and say, “I want a copy of FOIA 2018-200005, and they’ll send it to you really quickly because they’ve already redacted it,” Lipton said. “So you piggyback off of the work of others.”

Some federal agencies post responses at foiaonline.gov, so you can go online and search all the filed FOIAs and download completed responses.

As a freelancer, I understand why others hesitate to tackle FOIA. Filing records requests takes time away from paying assignments and other chores you need to manage to make sure you can pay the bills. But if you’re willing to make the initial effort to understand the law and figure out how to make it work for you, you may even get hooked on transparency. If you still need inspiration, consider the words of John Moss, who fought for over a decade to secure the rights of the public and press to inspect public records:

“Our system of government is based on the participation of the governed, and as our population grows in numbers it is essential that it also grow in knowledge and understanding. We must remove every barrier to information about—and understanding of—government activities consistent with our security if the American public is to be adequately equipped to fulfill the ever more demanding role of responsible citizenship.”

Further reading and resources.

CUNY Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism FOIA guide.

Environmental Data & Governance Initiative (EDGI). Analyzes federal environmental data, websites, institutions and policy with a mission to improve environmental data stewardship and to promote environmental health and environmental justice. EDGI cover four areas: 1) archiving vulnerable environmental data, 2) monitoring changes to information about the environment, energy and climate on federal websites, 3) interviewing federal employees about threats and changes to environmental health agencies, and 4) imagining, conceptualizing and moving toward Environmental Data Justice.

FOIA Wiki. A free, collaborative resource curated by Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, with contributions from The FOIA Project at TRAC, MuckRock, The National Security Archive, FOIA Mapper and Open the Government.

GovernmentAttic. Provides electronic copies of thousands of federal documents obtained under FOIA.

Journalist’s Toobox guide to FOIA resources.

MuckRock. File, track and share public records requests.

The Office of Governmental Information Services. FOIA ombudsman, provides oversight of federal agencies with congressional authority to review FOIA policies, procedures and compliance and identify ways to improve compliance. Resolves FOIA disputes between Federal agencies and requesters.

Poynter. Top 10 tips for getting public records.

Society of Environmental Journalists FOIA Fundamentals.

Society for Professional Journalists step-by-step FOIA guide.